If a violent man attacked your family, what would you do? Probably every Christian pacifist has been confronted with this question. The purpose of the question is to make the pacifist realize that violence is sometimes necessary: no matter how much you want to love your enemies, you may face situations in which refusal to use violence will lead to the harm or even death of people you love.

As John Howard Yoder points out in his book What Would You Do?, the questions is emotional. The attacker is always an anonymous man, and when the family members are specified, they are almost always a mother, daughter or wife. The one posing the question wants as little emotional bonds to the attacker as possible, while the opposite is true for the one being attacked.

Reality, of course, is not as simplistic. Most violence against women is conducted by people they know well. Questions that have even more relevance to what we might actually experience in life would be: what would you do if your son attacked his wife? Or what would you do if your mentally sick friend attacked an innocent stranger? But of course, these questions cannot easily be solved with “I use violence and everything become alright!” and so are left out of the picture.

Yoder goes on to point out that the one asking the question imagines two possible scenarios: you use violence and your family is saved, or you abstain from violence and your family is harmed. But there are many more possible scenarios at play. From a charismatic perspective, it should be self-evident that God can intervene or that we can confront demons influencing the violent person. Another scenario is that we try to use violence and fail. Yet another is that we block the attacker without hurting him, giving our family a chance to escape without causing any harm.

In this culture of violence that we find ourselves in, it is easy to assume that there are situations in which violence is the best or even the only option to solve a violent problem. In reality, research has shown that nonviolent resistance to oppressive power is far more effective than violent resistance, and we also know that if we try to use violence against a criminal or aggressor, they become even more violent compared to if we try to stop them nonviolently.

With all this being said, it is possible for the critic of pacifism to come up with even more thought-experiments that push the pacifist to the limit. What about if a terrorist is about to blow up 300 people – is it really forbidden for us to use violence to stop that? If we happen to be in a position where we can kill this terrorist, isn’t it far better and loving to kill one man rather than to let hundreds of people die?

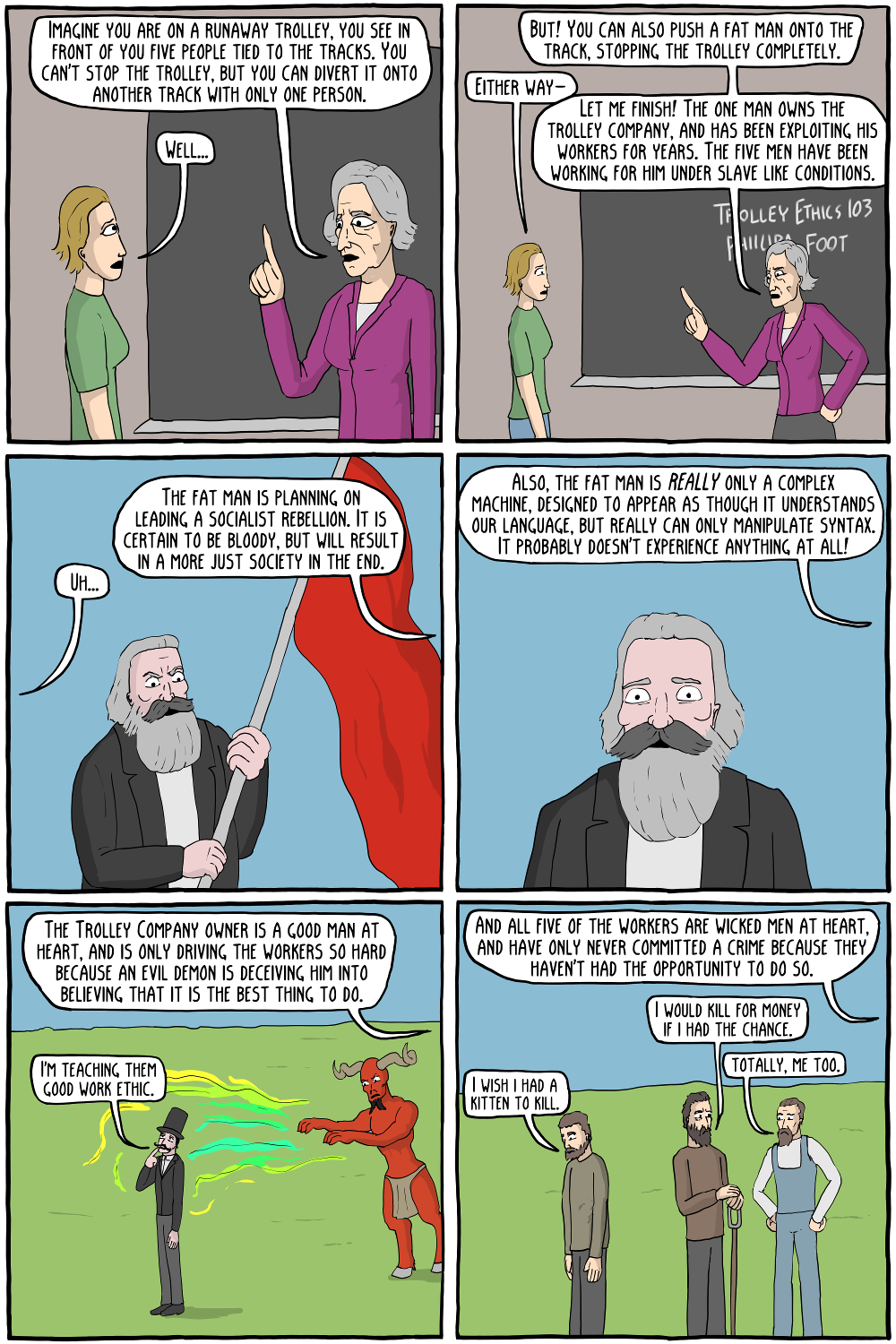

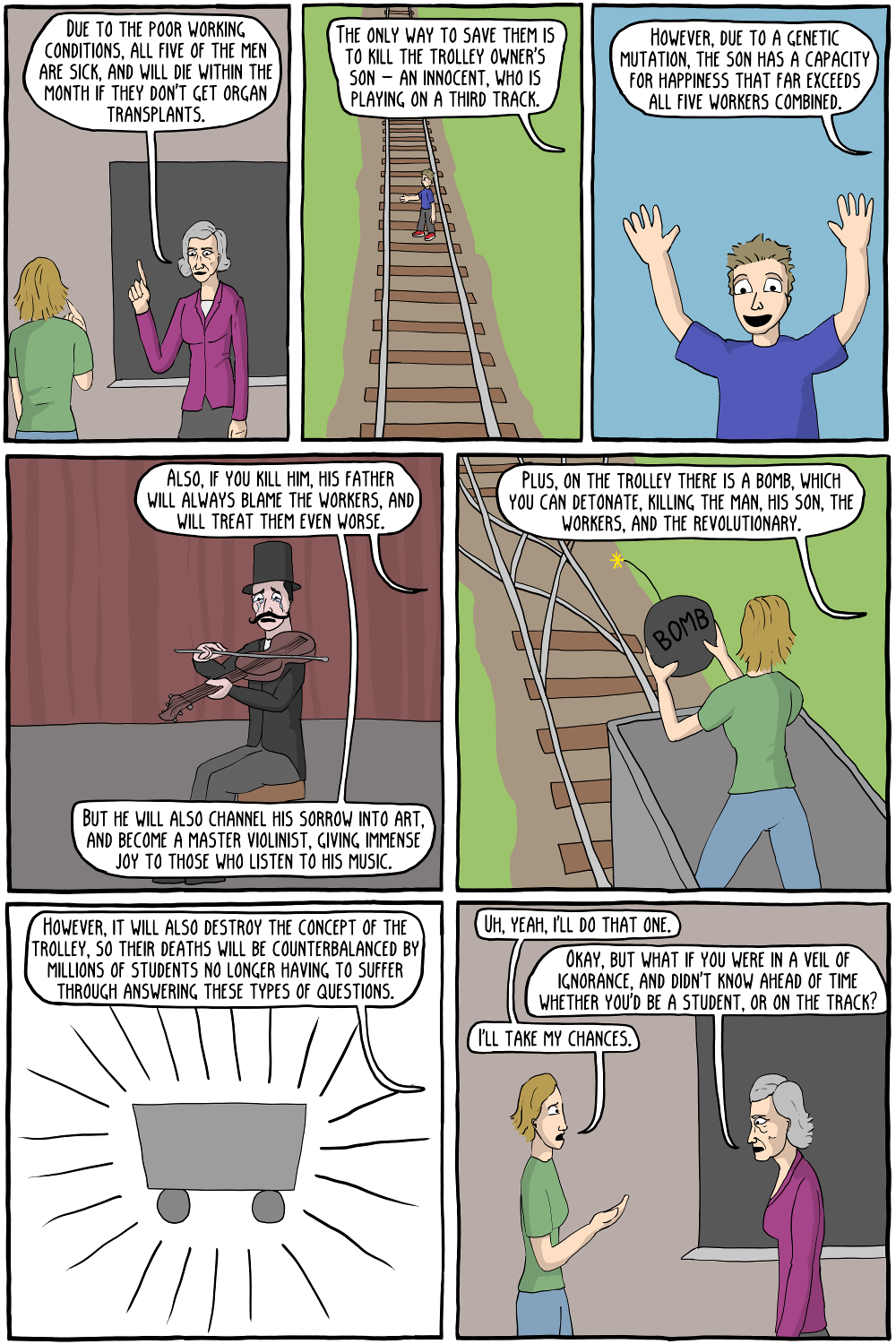

Do you know what this sounds like? The trolley dilemma.

The trolley dilemma is a very famous ethical thought-experiment, asking if it is right to actively kill one person in order to save five (or ten, or a hundred) others. As the comic above illustrates, it can be tweaked and wrestled with ad infinitum. Since trolleys are rare these days and hard to relate to, I prefer philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson‘s version which often is called the Doctor’s Dilemma:

A brilliant transplant surgeon has five patients, each in need of a different organ, each of whom will die without that organ. Unfortunately, there are no organs available to perform any of these five transplant operations. A healthy young traveler, just passing through the city the doctor works in, comes in for a routine checkup. In the course of doing the checkup, the doctor discovers that his organs are compatible with all five of his dying patients. Suppose further that if the young man were to disappear, no one would suspect the doctor. Do you support the morality of the doctor to kill that tourist and provide his healthy organs to those five dying people and save their lives?

The point of this dilemma is to put consequential ethics and duty (or virtue) ethics against each other. Most of us can agree that it is wrong to kill – one of the ten commandments explicitly states this – but the question is whether this principle can be overturned if the consequences of not following it saves even more lives than following it?

So what do you think that the doctor should do?

I’m guessing that most of you land in the same boat as I do: the doctor should refuse to kill an innocent patient even if that could save five more lives. Why? Some may appeal to the sanctity of life, others to the job description of a physician, still others to the will of God. But what I find very interesting is that one can reasonably motivate such a stance using consequential ethics.

Atheist debater Sam Harris demonstrated this in his debate with apologist William Lane Craig. Harris is, like many other atheists, a utilitarian. And he simply solved the doctor’s dilemma by pointing out the horrifying consequences in a world where you can’t trust whether your doctor will help you or murder you. No one would like to go to a hospital in such a world, which would lead to millions dying prematurely in diseases, far more people than doctors would ever save by becoming occasional assassins.

A similar logic can be applied to the trolley dilemma (assuming that trolleys are still around). The active murder of one person would save five, yes, but a world in which we encourage people to kill whenever they think that they would save others by doing so becomes a very violent and insecure world. The problem with the murderous doctor has now spread to the entire population, where even your own mother could send a lethal trolley your way if utilitarian logic demanded it.

I think America’s problem with gun violence clearly illustrates this. “Gun rights” activists often call for even more guns to solve the problem, so that even teachers are armed in some states today. They reason that the more “good guys” that have weapons, the quicker armed “bad guys” will be shot down. But of course, in such an environment, it’s easier for “bad guys” to acquire weapons, and so the US has become a league of its own when it comes to gun-induced homicide in the minority world:

While the logic of arming a teacher makes sense in the short-term perspective – they’re there long before the police and could potentially kill the school shooter before too many kids are harmed – the long-term consequences are disastrous. It creates a violent culture where every other citizen pretends to be a cowboy, and that leads to even more kids being killed in school shootings.

In most European countries, there are very few guns and very few mass shootings. We have another culture. It’s not perfect, but I think it’s quite obvious that it’s better than the distinctly more violent culture of the United States.

So this is ultimately my answer to the “What would you do”-question. I would intervene, I would pray and act in order to stop the aggressor from hurting anyone. I would even sacrifice my own life. But I would not kill. I would not cease to love my enemy. Because if I do, I participate in a disastrous culture of violence that leads to far worse consequences that the eventual tragedy that can occur if my nonviolent action fails.

It seems to me that it’s difficult for the non-pacifist to object to this while also explaining why a doctor should not kill patients from time to time in order to save other patients. If the long-term consequences of having nonviolent hospitals outweigh the short term benefits of occasionally saving more lives through killing the few, the same should apply to society as a whole.

It is always, whatever situation we find ourselves in, better to follow Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount than to make exceptions from it.

Micael Grenholm is a Swedish pastor, author and editor for PCPJ.

Pentecostals & Charismatics for Peace & Justice is a multicultural, gender inclusive, and ecumenical organization that promotes peace, justice, and reconciliation work among Pentecostal and Charismatic Christians around the world. If you like what we do, please become a member!

Pentecostals & Charismatics for Peace & Justice is a multicultural, gender inclusive, and ecumenical organization that promotes peace, justice, and reconciliation work among Pentecostal and Charismatic Christians around the world. If you like what we do, please become a member!

As far as the wife in the presence of a violent husband, I have seen many wives who with more discernment and foreknowledge could have prevented an explosion of temper etc. Prevention often starts in shuttle ways weeks or days before it happens. In fact all of us should look for ways to deescalate anger and violence in all of our relationships.

LikeLike

I don’t think this article fairly or with honest rationale truly proves its point. Is he suggesting that there is no place for violence at all? Or, that violence against violence should be a last resort?

It seems, according to this op ed, we should not have policeman, nor should we call on one when confronted with violence, nor should any Christian be a policeman.

This OP-ed is not taking life as it is seriously.

LikeLike