The late 1100s were a time of great social upheaval in Western Europe. Thousands left agriculture and migrated to the towns, which grew rapidly and a new ‘middle class’ of merchants and craftsmen evolved. Also, the Crusades had led thousands of men to their death, leaving an imbalance of women.

The Church was not well placed to cope with this new climate. For centuries, the beating heart of the faith had been in the monasteries, which were almost always in the country, sticking to ancient traditions and out of touch with new social developments. Women who wanted to live radically for God had few openings. The time was ripe for a new expression of the kingdom of God. A group called the Beguines rose to the challenge.

This was a spontaneous movement that began with a group of praying women in Liège, Belgium, in the 1190s. Not wanting either of the usual options of marriage or a nunnery, these radical women pioneered a new form of community. They pledged themselves to prayer, poverty and celibacy. Seeing how society was changing, they chose to stay in the towns, especially the poor suburbs, where they could serve the people with Jesus’ love.

Adult women during the Middle Ages were expected to live under the guardianship of a man, either within the household as a wife and mother, or dedicated to the Church as a nun. The Beguines deliberately lived outside of these boundaries. Women who entered Beguinages (Beguine houses and/or convents) were not bound by permanent vows, in contrast to women who entered convents. They could enter Beguinages having already been married, and they could leave the Beguinages to marry. Some women even entered the Beguinages with children.

They aimed to recover the simplicity, love and outreach of the early Church. They preached (which was not allowed), and in the language of the people, not Latin. Their communal settlements had a hospital, a place of worship, and work-shops for spinning, lace-making and other crafts that were to generate an income. They held literacy classes for poor children, supported widows, and took in orphans. And at every turn, they proclaimed God’s love for the poor.

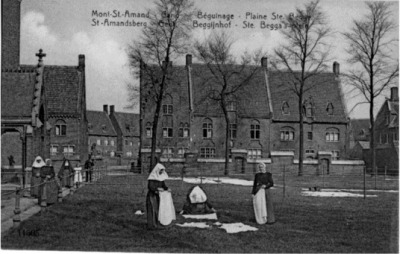

Beguines had no mother-house, nor common rule, nor any appointed head the order. Every community was complete in itself and fixed its own order of living. Members were of varied social status: some admitted only ladies of high degree; others only the poor; others again received women of every condition, and these were the most densely peopled. Several, like the great Beguinage of Ghent, in Belgium, numbered around a thousand.

In the beginning, the clergy’s attitude towards Beguines was ambivalent. They could not fault their chastity and charity, yet the fact that they existed without men (except for priests and confessors to lead them) was greatly mistrusted. They were never an approved religious order, yet they were granted special privileges and exemptions customary for approved orders. The Church, however, did not approve of their lack permanent vows. Women were not supposed to have that much freedom. In time, Beguines were treated as heretics and persecuted.

A male offshoot began, taking the name Beghards, but never made the same impact as the women – perhaps because they were not so very different from the Franciscan friars. It was the Beguines, the visionary women who created a visible kingdom of God, who made the lasting mark. They heard the pulse of the society God had placed them in, and met its need. The movement multiplied, and by 1270 there were Beguine communities in most towns in Belgium, Holland and North Germany.

FOR FURTHER READING

This piece gives more information (not that much is known) about Lambert le Bègue, parish priest of St Christopher’s in Liège in the latter part of the 12th century. He was a reformer who preached against abuses in the established church. It is generally assumed that the name Beguines was derived from his own, as it was he who urged a new movement of godly women who would rise up to serve their generation.

Here is a general sketch of the Beguine movement and its spirituality.

This more scholarly account discusses the characteristics of Beguine life and looks at the possible reasons for their eventual decline.

An article by Marianne Dormann looks further into the spiritual devotions of the Beguines, chiefly using The Mirror of the Soul, by Marguerite Porete, a French Beguine who was burned at the stake for supposed heresy in 1310.

For some old photographs and illustrations of Beguine houses, look no further than here.

Finally, in this piece, Marvin Anderson considers the contemporary implications of the Beguines’ rediscovery of lay ministry and grassroots evangelism.

Trevor Saxby is a mentor, pastor and PhD in church history. Author of Pilgrims of a Common Life and part of the Jesus Fellowship Church in the UK. He loves learning from the ‘movers and shakers’ of the past, as he wants to be one today!

Trevor Saxby is a mentor, pastor and PhD in church history. Author of Pilgrims of a Common Life and part of the Jesus Fellowship Church in the UK. He loves learning from the ‘movers and shakers’ of the past, as he wants to be one today!

This article contains false facts, for example the claim that it was illegal to preach in another language than latin.

In fact, the catholic church had required that the homily/sermon was in the vernacular if latin was not understod by the audiance. You can look up the council of Tours held in 813 ad about this.

The rest of the liturgy of the mass was held in latin however (except maybe some of the most common prayers and the Kyrie)

LikeLike

The variety of doable three dimensional figures is monumental,

so focus on those figures with frequent actual-life

applications https://math-problem-solver.com/ .

It read as a matter, however what does matter is that you should

choose specific dates and numbers that pertains to them.

LikeLike